St Godric, Hermit of Finchale

Murder of Thomas Becket on December 29,1170

Image from Liber Chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle)

by Hartmann Schedel, Nuremberg, 1493.

© Photos.com/Thinkstock

The murder of Archbishop Thomas Beckett in 1170 AD, at the hands of four knights in Canterbury cathedral, resulted in his enduring international veneration as a saint and martyr by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion.

The 850th anniversary of the crime was remembered in Britain and around the world. And in the last days of his presidency Donald Trump issued an official White House proclamation describing him a “lion of religious liberty.”

But there exists a much less-known link between St Thomas, Durham City and a holy man called Godric whose own extraordinary life ended in old age only months earlier.

Durham’s mystical saint, who lived as a hermit on the banks of the River Wear two miles east of Durham, was “adopted” by the Benedictine monks of the nearby cathedral. Venerated by the local peasantry and respected by the high-born, he was sought out by senior clergymen and religious scholars from across England.

He chose to live in austere self-imposed isolation in snake infested woodland at Finchale, determined to devote himself to God. But, his wish to be left undisturbed had eventually to be surrendered to stories of miracles, cures and extra sensory perception which punctuated his 12th century life – all meticulously documented over many years by Brother Reginald, a member of the nearby cathedral’s religious community.

When, after many years, Reginald sought blessing for a book about his life, Godric reluctantly gave it - only after the monk faithfully promised “never to speak of these things here written nor show them to anyone” until the day following the hermit’s burial.

The monk’s attention to detail, documented in writings covering this fascinating microcosm of life in the Middle-Ages remarkably survived the centuries. Not only did he mark the day of Godric’s death - on Thursday, May 21st, 1170 - but the time of his passing almost to the hour and the late spring sunshine that greeted the dawn!

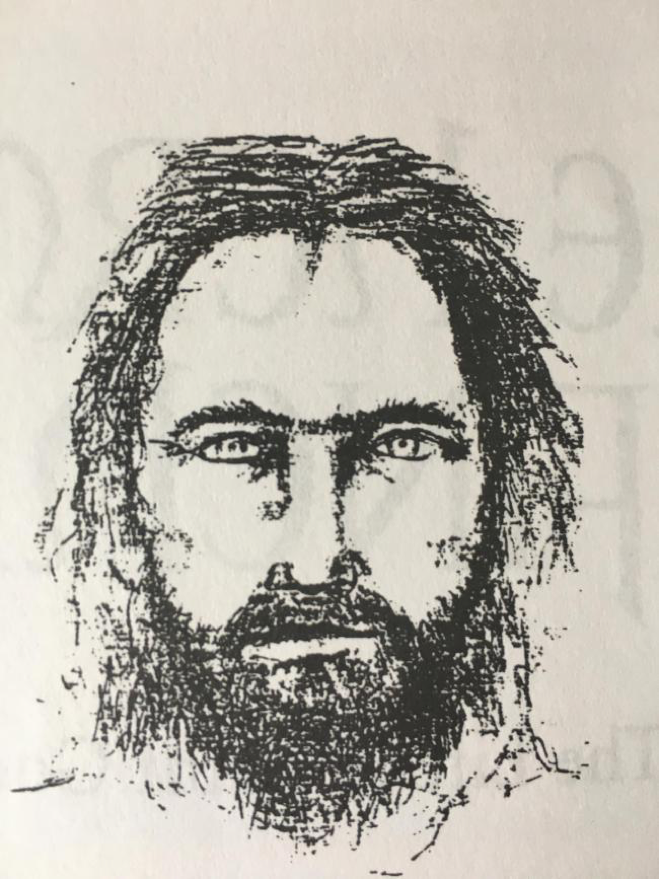

His striking description of his subject - in Latin - was outlined in a book written by Father Francis Rice, drafted after his retirement as priest-in-charge of the city’s St Godric’s RC Catholic Church. The details:- “a few inches” over five feet, his powerful build, “brilliant” grey-blue eyes, elongated thin face and shaggy eyebrows meeting over his nose - provided the basis 27 years ago for Durham Constabulary Detective Constable Bruce Burn, to pen a striking image now believed secure in a Vatican archive.

The image by Detective Constable Bruce Burn

The date of Godric’s birth in Norfolk to poor but pious parents, is put at sometime between 1065 and 1072. He worked as a pedlar before going to sea. His subsequent navigational skills earned promotion to ship’s captain and then on to successfully trading as a merchant up the North Sea coast and the near continent.

But his life was to take a dramatic turn. He chose to forsake the sea, sold his boat and became a pilgrim, his search for penance taking him to shrines across England, followed by trips to Rome and the Holy Land. On his return he totally and irrevocably committed himself to “seeking to find what God was calling him to do” and drifted north living as a tramp. His spent three years on the road before finally arriving in Durham to worship at the shrine of his adopted patron, St Cuthbert.

He was a regular attendee at Cuthbert’s tomb in the half built cathedral and in later life revealed it was during prayers the saint spoke to him and directed him to Finchale – although at the time he had no idea where it was or how to get there.

During his time in the city he was a doorkeeper at St Giles’ church, an appointment considered one of the first steps to priesthood and from there went to St Mary’s Church on the peninsular, studying as a mature student at the boy’s school.

The search for his nominated spiritual home finally came to an end after a chance meeting with two shepherds who he overheard talking of taking their flocks to Finchale. He offered his last penny to be guided there and on arrival disappeared into the dense woodland where he was to spend the next 60 years.

He levelled a plot of land by hand, built himself a cabin from tree trunks, with cross beams supporting a turf roof and added a door to keep out draughts. A chapel was later added and included a makeshift altar. Initially he survived on herbal roots and other foliage before tilling the ground and raising crops. Throughout his life he ignored the plentiful game and fish in the area and his frugal diet was a hallmark of his life.

Despite being desperate to be alone, his presence in the deep river gorge and intriguing lifestyle fuelled local curiosity before senior members of the Benedictines at the cathedral, including the prior, took particular interest in the holy man. They offered him spiritual guidance which was accepted, associate membership of their community and, in later life, the title of “brother.”

His constant battle between “the spirit and the flesh,” marked by his regular custom of standing naked up to his neck in river water at night in all weathers as he recited prayers and psalms, was endorsed by the monks.

They were, however, less forgiving of his “fanatical” dietary habits and his regular custom of cold-shouldering visitors who arrived unannounced, particularly on days when he was observing his rule of silence.

Godric long considered Finchale as God’s gift to him, a fact not formally recognised until he reached middle age and Bishop Flambard personally handed him ownership.

People, Reginald wrote, came in numbers to see him and left “uplifted in body and soul.” However, the same could not be said of marauding Scottish soldiers who arrived at his home around 1138 looking for plunder. They beat him roundly, at one point threatening to behead him, before destroying his hut and chapel and making their way back north. But, Reginald contended, all those involved in the desecration met an untimely end.

While many of his prayers were to St Cuthbert he was also devoted throughout his life to John the Baptist (he had immersed himself in the Jordan on one of his visits to the Holy Land). He reported many visions of Saint John who on one occasion appeared undistinguishable in a brilliant light, while in others spoke in words “sweeter than honey.” Similar experiences, according to Reginald’s chronicles, involved visions in which Jesus, the Virgin Mary and angels appeared.

St Godric praying, depicted in a 14th-century manuscript

© The British Library Board/Leemage/Bridgeman Images

However, one of the most striking events in Reginald’s writings involved the arrival of a frantic couple carrying a sack containing the body of their only child, a daughter. They dumped it at his feet and cried and pleaded with him to “bury her or bring her back to life.” The hermit told them they were asking the impossible and when further equally desperate pleas went unanswered the couple left.

Godric, deeply disturbed by the experience, finally knelt before his altar and prayed “frantically” and without interruption for three days, lying prostate before his altar and “shouting passionately aloud in his great agony of mind.” Finally, there was the sound of movement and he saw the child walking by the side of the chapel wall.

His first act was to send for the parents and on their return made them swear many times on oath that while he lived they would never divulge any part of the incident. The couple kept their promise and Godric only divulged his secret to his confidant monk when he lay seriously ill near the end of his life.

During his lifetime Godric made many accurate predictions of impending floods, disorder, famine, happiness and death. And his many successful cures too, built on his mystery. They embraced a wide range of ailments including fevers, tumours, persistent sickness, heavy bleeding, hearing loss, miscarriages and problems after child birth. The “medicine” he dispensed repeatedly favoured the offer of tiny pieces of bread or wearing fragments of cloth torn from his perished belt – all of them personally blessed.

His reputation spread across the country and people travelled long distances to see and hear him. During his last years, when he was laid low by the illness and disability of a long life of austerity, he became a confidant of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Although he and Beckett never physically met they communicated in secret, their messages relayed verbally by clergymen.

In one of his early exchanges Godric predicted the archbishop would be forced to flee into exile after a row with the king. In another, several years later, he again accurately forecast Beckett would be pardoned by the monarch.

When Godric died he was afforded the funeral rites normally reserved for Benedictine monks and after the ceremony a large crowd gathered to witness the body being laid to rest in a sealed tomb beneath his chapel. Nearly seven months later the archbishop was murdered on the steps of his own altar.

Finchale Abbey

Courtesy of Geoff Kitson Photography

In the years after his death the cathedral took responsibility for the shrine, often “alive” with visitors, and it was the monks who credited the mystic with no fewer than 225 miracles. Large among them were more than 30 cases of the restoration of sight – in one instance involving two brothers. There were also cures for lepers, the deaf, the dumb, chronic heart and stomach complainants and an extensive range of other serious ills.

But one particularly graphic incident involved a young knight called Lascelles, a member of one of England’s noblest families, who went to war in Normandy. In the thick of battle he was struck by a lance, inflicting a gaping wound in his stomach. The blood could not be staunched and soldiers who had gone to his rescue summoned a priest to deliver the last rites.

At the urging of those around the victim prayed “with sighs and tears” to St Godric to intervene. The soldiers marvelled as the nature of the wound changed before their eyes and a needle and thread lay on the ground to close the huge gash. The young man was reported strong and healthy three days later and later told the king of his deliverance. The knight and soldiers who witnessed the miracle, pledged to travel north to Godric’s shrine. About twenty five years later Finchale Priory was founded on the site of the hermit’s grave and thrived for 350 years until Henry V111’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in the mid-16thcentury. The priory’s ethereal ruins, maintained by English Heritage, stand in silent memorial.